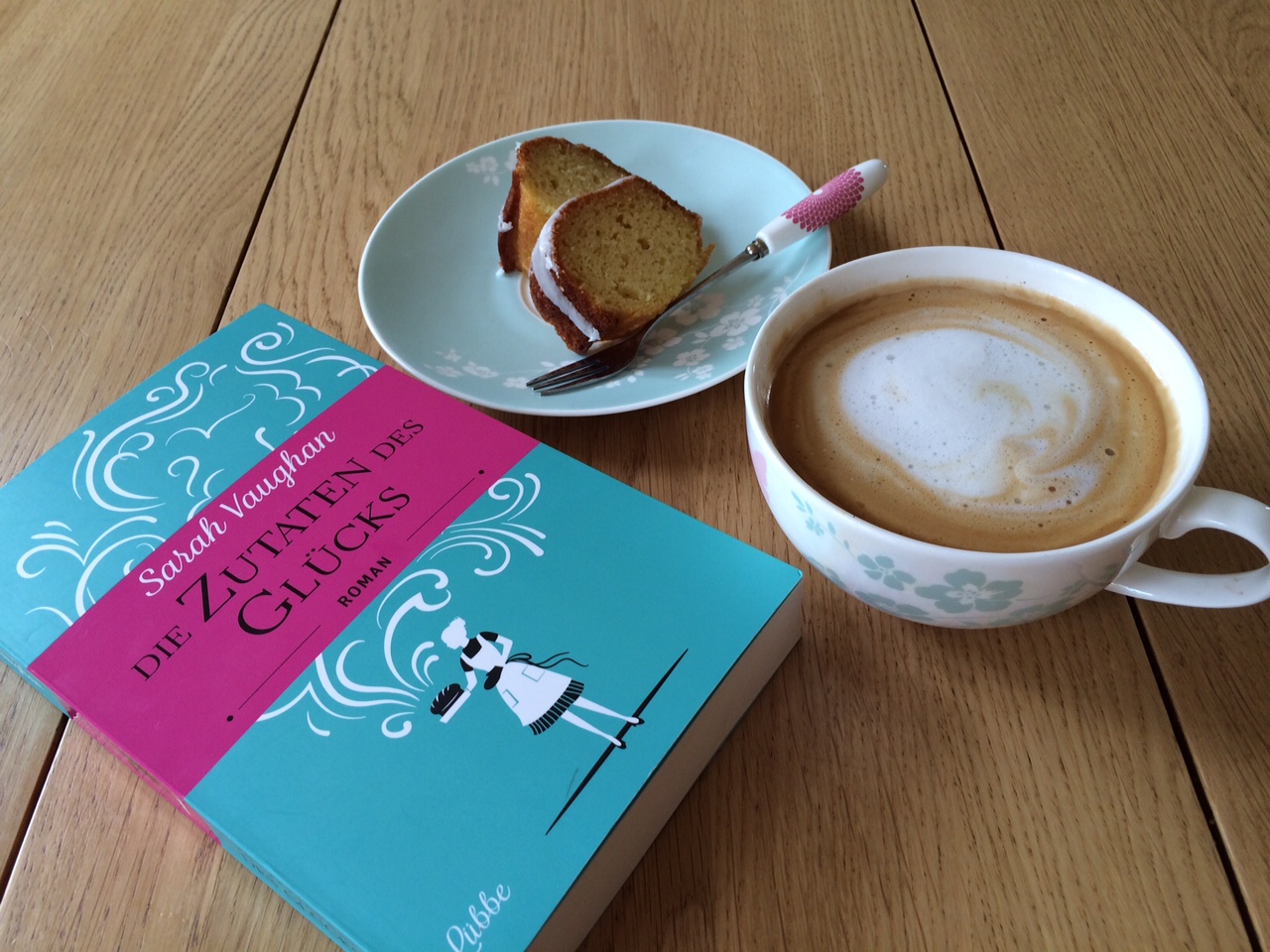

Happy Publication Day to the German edition of The Art of Baking Blind.

The Art of Baking Blind is published in Germany today as Die Zutaten des Glücks - or the rather lovely The Ingredients of Happiness. And as well as this being an opportunity to bake celebratory cheesecakes, black forest gateaux and my first ever bundt, it's made me contemplate fonts.

For while my German publisher Bastei Lübbe has used the same cover as Hodder, it departed from the original in using a different font for the sections in the past and a special letter-writing font for the one letter in the book. I love the changes but it's made me think about how we view the typography of novels.

When I submitted The Art of Baking Blind to publishers, I used italics for the quotations from The Art of Baking, the vintage cookery book whose bon mots top each chapter. But I also used italics for the flashbacks that intersperse the present day plot, which concern the cookbook's author Kathleen Eaden and run from 1964-66.

I wanted to clearly convey that these sections belonged to a different time and also differed in style, being exclusively from Kathleen Eaden's point of view. They were the most intensely emotional parts of the book and although they complemented the present day plot could be read as an individual story.

I hadn't considered, however, that while italics are routinely used to convey direct inner thoughts - most explicitly in a novel like Gone Girl - or for lists or letters, they signal to some readers that they can be skipped. The same could be said for any fonts used for meta-fiction. My 10-year-old, rereading the Harry Potter books, leaves out The Daily Prophet sections, the parts written in a heavy newspaper typeface. "They slow up the story," she explains. "My friends do it, too. We go back and re-read those sections if they're not explained later and we need to fill in the gaps."

None of this had occurred to me before Nina Stibbe, the bestselling author of Love, Nina and Man at the Helm, was kind enough to read a proof of my novel and pointed out the risks of sustained italicised sections. "I loved it but there's just one thing I don't like," she said. "The italics. You don't want people to skim them. Could you think about getting them changed?"

She was so persuasive that we reverted to the usual font with the sections being headed Kathleen. Bastei Lübbe didn't want to use our formula but came up with an excellent alternative: not using italics but a font which differs distinctly from the Times New Roman or Cambria we are used to seeing as the usual types. It's a technique also used recently in Marian Keyes' bestselling The Woman Who Stole My Life, in which the present day sections are in a more modern font to the back story set four years previously.

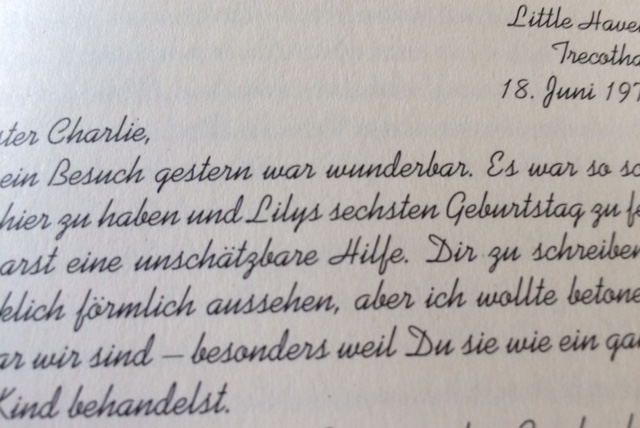

Bastei Lübbe also used a letter-writing font for the crucial letter on which Kathleen's story turns, which conjures up the era in which it was written, 1972:

As Iris Gehrmann, editor of fiction, explains: "We chose a different font for the Kathleen passages to distinguish her perspective from those of the other characters in the book. And the special handwriting font used for Kathleen’s letter at the end of the book is supposed to emphasize the very personal character of the document and its nostalgic flair."

All of which makes me wonder if I've become rather conservative not just in the way in which I react to fonts when reading but when writing. I tend to write in Times New Roman or Cambria, liking the implied authority and the way in which it is similar to the Sabon MT used by Hodder for my novel. In other words, the fact that it looks like a "proper" book.

Some authors switch to different fonts to edit: the change flagging up errors or prompting them to read in a fresh way. "I change font when I'm line editing. I think it helps me to spot errors more easily if I'm staring at a different typeface," Joanna Cannon, author of The Trouble with Goats and Sheep, to be published in the New Year, explains. That works for me but an experiment in writing in Helvetica this week took me way out of my comfort zone. Nothing that I'd written read or sounded right.

Perhaps I could learn from my seven-year-old who enjoys books which eschew the formality of a traditional font or subvert it - such as Andy Stanton's Mr Gum books, in which smudged fingerprints or decreasing and increasing font sizes pepper the page - or which reject the authority of a typed text and appear to be handwritten. "Why do you enjoy the Wimpy Kid books so much?" I ask my boy, as he pores over the latest instalment after reading Tom Gates. "Because there's more space around the words," he explains as if it is perfectly straightforward. "They're easier to read."

It seems I may have been too precious in my attitude to fonts. I tweet Marian Keyes to ask her about her use of them in The Woman Who Stole My Life and she quickly gets back to me. (She's fiendishly good at and prolific on twitter.)

"Why don't you play around with those available to you and see what ones appeal?" she asks - opening up all sorts of future possibilities. "Have fun with it."