The young man formally acquitted of murdering the black teenager Stephen Lawrence stood just over a metre from me in the witness box - and smirked.

It was February 1997. I was 24, had been a trainee reporter for just over a year, and as the only member of the press present at the very start of the inquest into the black teenager’s death was scribbling away at the old-style wooden press desk just in front of him. I looked up: pen poised, hoping for an intro-worthy line with which to nose my story. He remained silent. And then his lip curled.

Neil Acourt, his brother Jamie, and the other members of their gang, Gary Dobson, David Norris, and Luke Knight, had maintained what the QC Michael Mansfield would describe as a “wall of silence” during the inquest, repeatedly claiming the common law right of privilege so as not to risk incriminating themselves. But their continued repetition of the phrase gradually polluted the atmosphere of that dark Victorian coroner’s courtroom, so that it shifted from the ridiculous to the dramatic and taut.

As the QC drove on, his questions acquired a hypnotic rhythm while the young men’s stonewalling and swagger conveyed their acute lack of compassion and exposed them, in the words of the Macpherson inquiry, as “the prime suspects” for the racially motivated crime. A year into a career that would see me covering murder trials and sexual abuse trials at crown courts and the Old Bailey, I saw at first hand the inherent drama, the high stakes and extremes of emotion that could be played out in court.

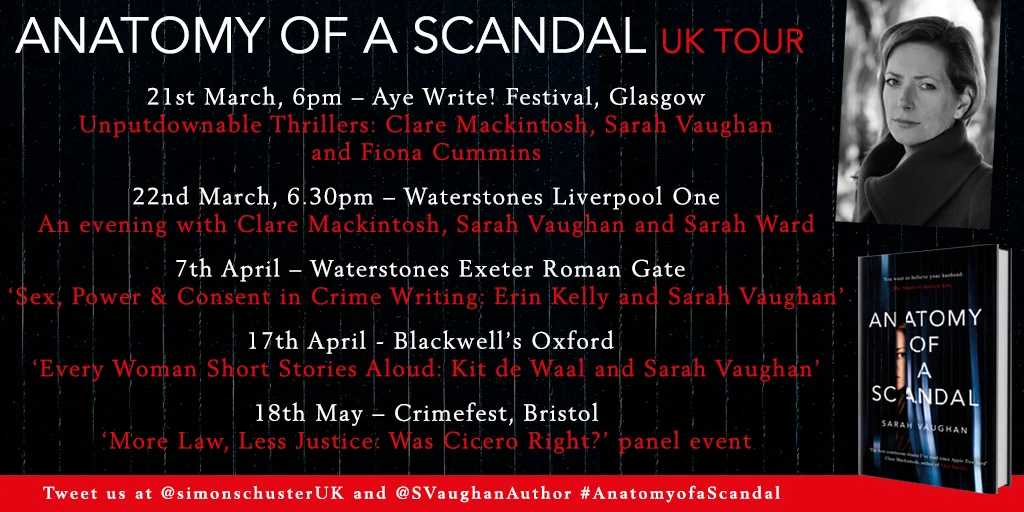

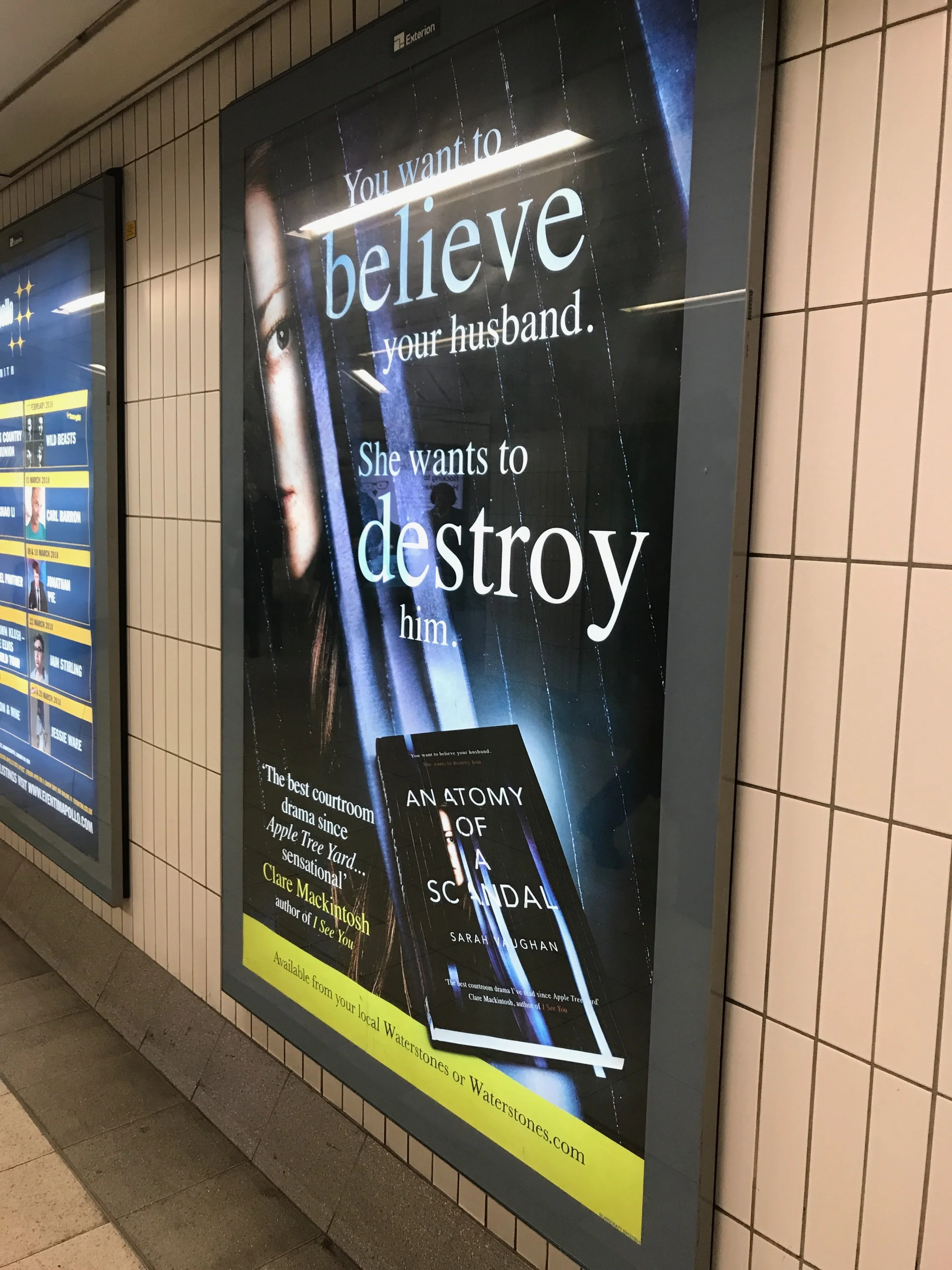

If my day in that coroner’s court illustrated the power of a courtroom drama – a power I’d try to harness nearly 20 years later when I came up with the idea of Anatomy of a Scandal - my experience covering criminal investigations such as the Soham murders confirmed how a narrative can turn on a comment, or a plot twist and then veer off course.

Eleven days after the 10-year-old schoolgirls Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman disappeared from their tiny Cambridgeshire town, the caretaker of the local secondary school, Ian Huntley, told a journalist colleague he might have been “the last person to see them alive.” When the East Anglia correspondent for the Press Association asked to take a photo so that the story could be syndicated around the UK, and a TV reporter asked to film him, Huntley became shifty. And by the time I was begging him for an interview, he stood, arms crossed and immovable.

His behaviour – sparked by a fear that police in Grimsby might remember his predilection for young girls and three alleged rapes, might recognise him - rang alarm bells with journalists and detectives, and late on the Friday afternoon, 12 days after the girls’ disappearance, the police called a press conference to say that a man had been arrested.

“It’s the caretaker.” The whisper spread through the assembled hacks, as we noticed that the ubiquitous Huntley was absent from his usual spot at the back of the school hall. The man who’d kept an eye on police proceedings, during press conferences for nearly two weeks, who had tried to court and manipulate the media, had been undone by his cockiness.

But while courtrooms and murder investigations helped me to write a thriller, it was through becoming a political correspondent that I became even more conscious of power, privilege and entitlement - all issues at the heart of Anatomy of a Scandal. I watched charismatic, psychologically complex characters at work - and saw how the truth could be obscured. Nuance of language became increasingly important as Number 10 countered allegations that they had “sexed up” of the dossier into weapons of mass destruction. “Off-the-record” and “deep background” introduced layers of meaning beneath the official line.

The theatre of the courtroom was replaced for the theatre of the Commons chamber. Bound by the same rules of privilege, the stakes were high – not prison, but reputation - and robust egos were now thrown into the mix.

I witnessed moments of high tension. The resignations of cabinet ministers Peter Mandelson, over the Hinduja affair, and Robin Cook, over Iraq. Ken Clarke’s blistering speech during the debate into whether we should go to war. Most powerfully, I was with Tony Blair, on a trip to Istanbul, when the news broke that the former weapons inspector Dr David Kelly had committed suicide. I watched the blood drain from the prime minister’s face as a tabloid journalist asked him: “Do you have blood on your hands?”

I also saw how sex scandals involving politicians broke and played out. I was in the lobby when the Home Secretary David Blunkett was exposed by the News of the World for having an affair with the publisher of the Spectator; and I saw Boris Johnson colourfully deny and later admit to lying over, his affair with Petronella Wyatt.

Working on news stories showed me how the media generates and drives the news agenda – something that has intensified since my days in the lobby with the arrival of social media and 24-hour news coverage. Alistair Campbell famously said that if a story was on the front page for over a week – 8 to 10 days, the figure’s been debated – the minister would have to resign. Though political expediency means some ministers currently seem untouchable, I suspect the period would now be shorter.

All of this fed into my writing Anatomy of a Scandal – a novel I couldn’t have conceived without that experience of working in the lobby, or those early years of court reporting, when I sat, straining to capture each choice quote in 110wpm shorthand.

Westminster inspired me but perhaps the idea of writing a novel that’s part courtroom drama and part psychological thriller, came from that moment in Southwark coroner’s court, when I witnessed the power of a QC’s examination – and a story conveyed by the absence of words.